EIB #13 - Losing Money by Minting Money

Today's revision to Q1 real GDP, federal outlays are still above their pre-pandemic trend, the possible consequences of raising the debt limit in small increments, and questions from the mailbag.

All,

In today’s EIB, please find:

Key Takeaways on Today’s Revision of Q1 Real GDP Growth

Revised up; Still slightly negative, but not statistically different from zero.

Federal Outlays Remain About $1.2 trillion Above Pre-Pandemic Trend

The Consequences of Raising the Debt Limit in $500B Increments

Email chris@russoecon.com with questions, suggestions, or to request a briefing or testimony. Feel free to forward or subscribe (it’s free). Thanks for your support!

Best,

Chris

P.S. As of writing late last night, the U.S. Court of International Trade ruled that Pres. Trump does not have the power to impose tariffs under IEEPA.1 The Court set aside most of the tariffs imposed by the Trump admin. I flagged this case in EIB #9.

In the morning, I expect U.S. equities and U.S. Treasuries to rally on the news. This case will be appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and (I suspect) ultimately decided by the Supreme Court. Continue to watch this play out.

Key Takeaways on Today’s Revision of Q1 Real GDP Growth

At 8:30am ET, the BEA announced revisions to its estimate of Q1 real GDP.2

Real GDP growth was revised up to -0.2% (vs. an initial estimate of -0.3%). This decrease is less than 0.1% at a quarterly rate. (Not statistically different from zero.)

Inventories were revised up. However, this was partially offset by a downward revision to consumption, reflecting revisions to both goods and services.

BEA also announced its estimate of Q1 real gross domestic income (GDI).3

Real GDI growth printed at -0.2%.

The average of real GDP growth and real GDI growth was -0.2%.

The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model estimates that Q2 real GDP growth is 2.2%.

While the stock market is not open as of the time of writing, equity futures are rallying. S&P 500 futures are up 0.8%. Treasuries are also rallying, with the on-the-run 10-year now trading at a yield below 4.5%. (Prices move inversely to yields.) This comes on the news that a federal court has set aside most of Pres. Trump’s tariffs.

Federal Outlays Remain About $1.2 trillion Above Pre-Pandemic Trend

The Senate will now consider the reconciliation bill, which narrowly passed the House last week.4 The bill as currently written likely does not have 50 votes in the Senate.5 Republicans have a 53-47 majority and can only afford to lose three votes.6

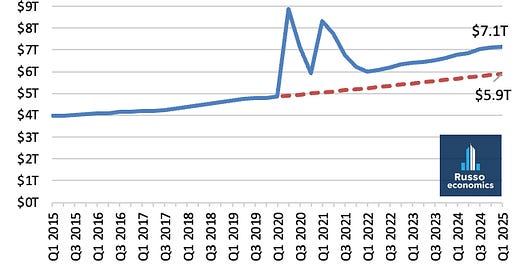

One dissenter is Sen. Johnson, who argues that federal spending should be reduced to between $5.5 trillion and $6.0 trillion per year. He claims this range is based on pre-pandemic federal spending adjusted for inflation and population growth. I get similar numbers by extrapolating pre-pandemic spending levels to today.7

A return to the pre-pandemic (and pre-Pres. Biden) trend of federal spending is a commonsense goal for Republicans. Given that current federal spending is about $7.2 trillion per year, this amounts to a reduction of $1.2 trillion to 1.7 trillion per year.8 Achieving this would slash the deficit and stabilize the near-term debt-to-GDP ratio.

However, this would require members to trade off between competing priorities. The political problem is that Republicans cannot agree on priorities; and to the extent they can agree, they agree to not touch the mandatory spending programs driving the long-run growth of the debt-to-GDP ratio (i.e., Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid).9

So Congress is largely left to twiddle with discretionary spending. In FY2024, non-defense discretionary spending amounted to about $0.9 trillion. In other words, Congress could eliminate every dollar of non-defense discretionary spending and would still fail to reduce outlays by $1.2 trillion to $1.7 trillion per year.

The Consequences of Raising the Debt Limit in $500B Increments

Another dissenter is Sen. Paul, who described the House cuts as “wimpy and anemic.” Compared to a goal of $1.2–1.7 trillion per year, I take his point. Excluding the Ways and Means title, the House bill would cut about $150 billion per year. That is only about one-tenth of the amount sought by Sen. Johnson and other conservatives.10

Sen. Paul’s main objection, though, is that the bill would raise the debt limit by $5.0 trillion. Based on very rough math, this would allow Treasury to continue to borrow into FY2027.11 The debt limit would not need to be raised until after the midterms.

Sen. Paul instead suggests raising the debt limit by $500 billion, and continue to raise the debt limit in $500 billion increments while Congress hashes out more cuts. While I do not expect the House Republican Conference or Senate Republican Conference to take this proposed approach, it is worth thinking about its potential consequences.

Based on the very rough math above, raising the debt limit in $500 billion increments would require raising the debt limit every few months.12 The immediate difficulty is that (under current rules) Congress is restricted to one reconciliation bill with a debt limit impact per fiscal year. Hence, for the rest of FY2025 and all-but-once in FY2026, Republicans would need support from Senate Democrats to raise the debt limit.

Suffice to say, Senate Democrats would not be motivated to help Republicans out of this quagmire. The result would be that, following the “X Date,” the Treasury would be unable to borrow to meet all of the government’s lawful payment obligations, and it would likely begin “prioritizing” its incoming revenue to certain outlay line items.

What payments would be prioritized? I would expect that Treasury would continue to make all principal and interest payments, rolling over marketable debt at auction. I would also expect Treasury to continue to pay all Social Security and Medicare benefits. Presumably, Treasury would also continue to pay for active-duty military salaries, certain veterans’ benefits, certain national defense functions, and the courts.

Beyond that, who knows? One difficulty of using the debt limit as an ex post facto tool of fiscal discipline is that it requires articulating extremely detailed spending priorities. If Republicans could articulate such detailed priorities, then the appropriate place to implement those priorities would be the budget process.

Mailbag

The U.S. Mint is phasing out the production of pennies. Will this be inflationary?

No. Prices will just get rounded up or down to the nearest five-cent increment. The federal government will save a tiny amount of money.13 We should nix the nickel next, which is an even bigger loser. Only the government could lose money minting money.

What does it mean for the U.S. dollar to be the “world’s reserve currency”?

Prior to WWI, much of the West was on the classical gold standard.14 Coins were made of (and banknotes were backed by) specific quantities of fine gold. The relative gold content of the coins and notes fixed the exchange rate between them. The gold standard fell apart during WWI. Despite attempts to revive it during the interwar period, countries ultimately abandoned the gold standard during the Depression.

Following WWII, politicians and economists devised the Bretton-Woods system to return to a quasi-gold standard. Under this system, the U.S. (which held the bulk of the world’s gold reserves) would back the dollar with a specific ratio of fine gold. In turn, participating countries would each back their currencies with a specific ratio of dollars. Hence, under Bretton-Woods, the dollar became the world’s reserve currency.

Bretton-Woods itself fell apart decades ago. The death knell came when Pres. Nixon suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold in 1971. The relative value of different currencies was no longer fixed by their relative backing of U.S. dollars.15 Rather, exchange rates floated based on interest rates, inflation, and other fundamentals.

Even so, countries continued to hold reserves of U.S. dollars and Treasury securities for a variety of reasons (e.g., to signal they are fiscally responsible). The end result is that there is a large overseas demand for U.S. dollars and U.S. Treasuries by the foreign official sector. A few countries even use the dollar as their own currency.

Nevertheless, there is no general legal obligation for countries to back their currencies with U.S. dollars. Our “reserve currency” status is unofficial. Countries can (and do) diversify their reserve assets with other currencies, bonds, and commodities.

Upcoming Data Releases

June 6, 8:30am ET. The BLS will release the jobs report for May 2025. All eyes will be on any potential impact from tariffs. I will also provide an updated RecessionWatch.

June 11, 8:30am ET. The BLS will release the CPI report for May 2025. Will this be the fourth consecutive month that inflation falls back towards the Fed’s 2% target? The Cleveland Fed nowcast suggests that 12-month inflation will tick up to 2.4%.

June 18, 2:00pm ET. The Federal Reserve announces its monetary policy decision. The current target range for overnight interest rates is 4.25% to 4.50%. Owing to solid job growth, above-target inflation, and high uncertainty about tariffs, options markets are pricing a nearly 100% chance that the Fed will keep the target range unchanged.

The Court did not set aside the Section 232 tariffs on aluminum, steel, and autos, which were not at issue in the cases before it. This is a different legal authority than IEEPA.

All numbers in this section are expressed at a seasonally adjusted annualized rate, except where otherwise mentioned.

In principle, real GDP growth should equal real GDI growth. In practice, they differ because they are measured using different data sources and statistical methods. Hence, real GDI growth serves can serve as a “sanity check” on real GDP growth.

The bill passed 215-214, essentially along party lines.

Current no’s include Sens. Johnson, Paul, and Rick Scott; as well as possibly Sens. Hawley, Murkowski, or Collins. Expect some significant changes to bring these and other members onboard. Among other things, I expect a reduction to the SALT cap.

Assuming full member attendance. VP Vance would break a tied vote in favor of passage.

I assume a one-percent annual increase in annualized federal outlays, which is the (arithmetic) average growth rate of annualized between Q1 2014 and Q4 2019.

As a point of comparison, the House Republican Study Committee FY2024 budget proposed cutting outlays by about $14 trillion over the 10-year window, which would meet this goal.

Interest expense on the national debt is also a key driver of the long-term debt-to-GDP ratio. I omit this besides (aside from default) Congress cannot directly reduce this spending. It can also be reduced indirectly through slower growth in federal debt, and responsible debt management that finances the national debt at the lowest cost over time.

Including the W&M title drives the bill from deficit reduction to deficit increase.

CBO’s Jan 2025 baseline projects total deficits of about $1.7 trillion in both FY2026 and FY2027. CBO’s score of the House bill implies that the deficit will be at least $1 trillion higher during those first two years. (This is a total figure for both fiscal years, excluding interest and unscored interactions between bill titles.) Moreover, Treasury could need to borrow up to $1 trillion to restore its cash balance to its prior pre-cautionary levels.

$1.7 trillion + $1.7 trillion + $1 trillion + $1 trillion = $5.4 trillion

So, the House would raise the debt limit by $5 trillion, and this would be exhausted sometime in the middle of FY2027. (This fiscal year runs Oct 2026 to Sep 2027.)

I stress that this calculation is very rough. For example, I ignore the dynamics of Social Security and Medicare trust fund. Payments for Social Security or Medicare Part A involve a “redemption” of non-marketable Treasury securities held in the trust fund accounts. These non-marketable Treasury are essentially an internal accounting procedure to track the amount that these programs have historically received tax revenues above their outlays.

These non-marketable Treasury securities are counted against the debt limit and are redeemed when Treasury makes a payment to a beneficiary. Treasury will issue a marketable security to the public to finance the payment. Hence, the net effect of a Social Security or Medicare Part A payment on total federal debt subject to the debt limit is zero.

Conversely, this calculation also ignores the role of “extraordinary measures,” which are essentially accounting gimmicks provided by Congress to allow Treasury to continue to borrow for a limited time after reaching the debt limit. These extraordinary measures involve the “redemption” (not really) of certain kinds of non-marketable debt subject to limit. This frees up room under the debt limit for additional marketable borrowing. In turn, when the debt limit is raised, those “redemptions” are undone and count against the limit.

God bless anyone who actually read this footnote.

The need to raise the debt limit would not be uniform. The government runs surpluses in some months and deficits in other months. (But on average, the government runs a deficit!)

“Tiny” in the sense that $56 million per year in savings is rounding error compared to roughly $7 trillion in federal expenditures. (For perspective, a trillion is a million millions.) Nonetheless, it is wasteful, and it is morally right to eliminate waste from federal outlays.

Scholars of the gold standard will (appropriately) nitpick me here. I am glossing over a swath of details/controversies for brevity.

Whether this was a good thing is subject to debate. Milton Friedman famously supported floating exchange rates, which would decentralize monetary policy to the national level. Countries with floating exchange rates could (in principle) use monetary policy to manage the business cycle by buffering the economy from shocks to aggregate demand. However, in conducting such policy, Friedman generally envisioned a rules-based monetary policy.

An alternative argument in favor of fixed exchange rates is that floating exchange rates tend to be overly volatile. That is, there is some news about inflation in Country A’s domestic currency prices, and there is a corresponding move in the exchange rate between Country A’s domestic currency and Country B’s domestic currency. If those movements tend to be “too large” compared to what the fundamentals would justify, then this result in economically inefficient changes to trade and capital flows.