EIB #17 - Eliminating Interest on Reserves

BEA revises down its estimate of Q1 real GDP growth, Sen. Cruz proposes eliminating paying interest to banks for their reserve balances, and I answer related questions.

All,

In today’s EIB, please find:

Feel free to forward or subscribe (it’s free). Thanks for your support!

Best,

Chris

Key Takeaways from Today’s Revision to Q1 Real GDP

At 8:30am ET, the BEA announced revisions to its estimates of Q1 real GDP, etc.1

Real GDP growth was revised down to -0.5% (v. the prior estimate of -0.2%).

Downward revisions to consumer spending and exports were only partially offset by a downward revision to imports.

The finance and insurance sector contributed the most to the decline in real GDP, followed by agriculture, wholesale trade, and retail trade.

Real final sales to private domestic purchasers was revised down to 1.9%.

The prior estimate was 2.5%, while the initial estimate was 3.0%.

Excludes the volatile categories of inventories, net imports, and government.

Real GDI growth was revised up to 0.2% (v. the prior estimate of -0.2%).

The average of real GDP growth and real GDI growth is -0.1% (v. -0.2% before).

The downward revisions to real GDP and real final sales to private domestic purchasers are not good signs for the U.S. economy. That said, the upward revision to real GDI is a welcome sign. The average of real GDP growth and real GDI growth even ticked up. Ultimately, though, these small revisions do little to change my outlook.

Sen. Cruz Wants to Eliminate Interest on Reserves

Chairman Powell’s public comments were characteristically mild, but I’m confident the Fed has been forcefully lobbying against this proposal in private.

However, so long as the Fed has time to transition, ending interest on reserve balance (IORB) need not be catastrophic. The Fed would shrink its balance sheet by selling off trillions of dollars of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities bought during QE. This would soak up the supply of excess reserves it had pumped into the banks.

Without excess reserves, the Fed would not need IORB to control overnight interest rates. The Fed could control overnight interest rates as it did before the financial crisis: using open market operations to adjust the supply of reserves relative to demand. The Fed would have a smaller footprint, both in markets and in politics.

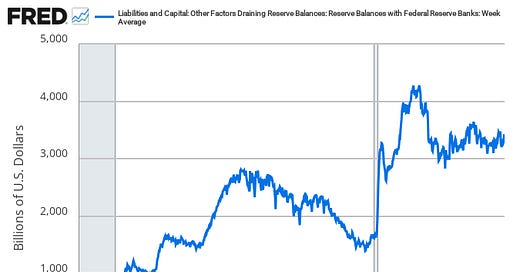

The trillion dollar question: Would eliminating IORB save money? The cheeky answer, best articulated by Sen. Johnson, is that IORB is just “free federal money.” So, take the level of reserves ($3.32 trillion) and multiply it by the IORB rate (4.4%).2 That’s about $133 billion in savings per year, or a 10-year savings of $1.33 trillion.3 Winning!

With great respect for Sen. Johnson, I disagree with this framing for two reasons.

Reserves are government debt. Paying interest on reserves is no more “free federal money” than paying interest on Treasuries. Not paying IORB is an implicit tax on banks. That was Congress’s original intention behind authorizing IORB.

While the Fed would stop paying interest on reserve balances, its smaller portfolio would generate substantially less interest income. Historically, the Fed has had a positive net income, which it remits to Treasury. The Fed’s positive net income is due to its long-term assets tending to pay higher interest than its short-term debt.

That said, in a world of scarce reserves, the “implicit tax” of not paying IORB is relatively small. Before the financial crisis, the aggregate level of reserves was about $40 billion. Assuming an IORB rate of 3%, the implicit tax would be $1.2 billion per year. By comparison, the U.S. banking sector had an annualized profit of $282 billion during Q1 2025. That works out to about a 0.4% tax. Not great, but not a catastrophe.

Moreover, the Fed’s net income is highly risky. The Fed is essentially engaged in the carry trade: financing long-term fixed income assets with ultra short-term debt. When short-term interest rates remain low, the Fed earns a profit from the positive spread between long-term rates and short-term rates. But as we have recently seen, short-term rates can rise! The expression is “picking up pennies in front of a steamroller.”

Hedge funds in the carry trade attempt to hedge this risk using risk management strategies. Unlike the Fed, a hedge fund will not lever up 150x and “HODL.”4 That is an easy way to go insolvent; and indeed, the Fed is insolvent on a market-value basis. The Fed picked up a lot of pennies over the years, but got run over by the steamroller.

After a string of profits, the Fed has suffered operating losses of roughly $224 billion since October 2022. If interest rates remain high, then losses will continue to accrue.

This has a fiscal consequence for the federal government. When the Fed purchases Treasuries financed by new reserves, it refinances long-term government debt into ultra short-term government debt. When short-term interest rates later rise, the result is an economic loss to the taxpayer. The deficit would have been lower otherwise.

From this perspective, I think Republicans have a colorable argument that ending IORB would generate meaningful savings. Indeed, Treasury’s guiding principle for debt management is “least cost over time.” Meanwhile, the Fed’s own focus is on monetary policy, not the impact of its own financial performance on taxpayers.

Insofar as the Fed’s Treasury QE purchases distort the maturity structure of government debt away from “least cost,” the Fed increases costs over time.5

Mailbag: Questions about Eliminating IORB

I’ve received some questions about Sen. Cruz’s proposal. I think these questions underscore that the proposal is workable, but the Fed would need some runway.

Does the Fed have enough assets to soak up reserves? Or would it need a bail out?

No bailout needed. The question stems from the fact that the Fed is insolvent on a market-value basis (i.e., the market value of its liabilities exceeds the market value of its assets). Reserves are the Fed’s primary liability. The concern is that the (now lower) market value of the Fed’s portfolio would be insufficient to soak up excess reserves.6

Doing the math, though, I am not concerned. As of June 18, the Fed’s securities portfolio had a par value of $6.37 trillion. A reasonable estimate is that the Fed’s portfolio has a market value of about $5.37 trillion (or about a $1 trillion discount) due to higher interest rates. That’s enough to soak up the Fed’s $3.32 trillion of reserves.

How would Treasury need to change its cash management policy without IORB?

Since the introduction of excess reserves and IORB, Treasury has held all of its cash balances in its Treasury General Account (TGA) at the Fed. The TGA is highly volatile.

Without IORB, Treasury would need to actively manage the size and volatility of the TGA. This is because payments to the government increase the TGA and decrease reserves; while payments from the government decrease the TGA and increase reserves. Without Treasury managing this volatility, the Fed would find it difficult to manage the aggregate supply of reserves to set overnight interest rates.

Presumably, Treasury would need to return to the prior system in which it held the bulk of its cash balances in the private banking system. That way, payments to/from the government had a more minimal impact on the aggregate level of reserves.

Given lower levels of reserves, would the Fed need to modify any liquidity regulation?

I do not believe so, although banking lawyers will need to weigh in. To my understanding, current U.S. liquidity regulation treats reserves and Treasuries in the same way. E.g., both reserves and Treasuries are tier 1 high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) for the purposes of calculating a bank’s liquidity coverage ratio. The lower level of reserves would be offset by the higher level of Treasuries held by the public.

That said, from past conversations with market participants, I understand that some banks feel their supervisors have an implicit preference for reserves over Treasuries. Supervisors would need to clearly and credibly articulate that no such preference exists. Given a scarce level of reserves, tier 1 HQLA will need to be mostly Treasuries.

Upcoming Data Releases

July 3, 8:30am ET. The BLS releases the jobs report for June. While initial numbers have surprised to the upside, jobs added have been revised down by 189,000 since Jan.

July 15, 8:30am ET. The BLS releases the CPI report for June. The Cleveland Fed nowcast is 0.25% m/m (2.64% y/y), implying that inflation is still above target.

July 30, 8:30am ET. The BEA releases its “advance” estimate of real GDP for Q2. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model estimates real GDP growth is 3.4% (SAAR).

Figures in this section expressed at a seasonally adjusted annualized rate.

The current level of reserves is taken from the H.4.1 report on 06/20/2025. See Table 5 (continued) and the liability titled “Other deposits held by depository institutions.”

To be a bit more serious: the IORB rate is expected to fall over time as the Fed cuts interest rates. Therefore, assuming a 4.4% IORB rate for the full 10-year window likely overstates the interest expense the Fed will pay on reserves. According to the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections, the median FOMC participant expects a longer-run effective fed funds rate (EFFR) of 3.0%. An IORB of 3.0% works out to a 10-year savings of $1.0 trillion.

One could further complicate this by modeling the IORB rate falling from its current level to the expected longer-run level, as well as model the declining (and then rising) level of reserve over the 10-year window. I don’t think the answer would be qualitatively different.

“150” is approximately the ratio of the Fed’s assets (par value) to its pro forma capital.

One could argue that QE stimulates a faster economic recovery when interest rates are stuck at zero. A faster economic recovery would generate more government revenue, and one would want to include this revenue when scoring the eliminating of IORB. This argument makes logically sense, but I think the economic impact of QE is quite small.

For simplicity, I am ignoring other reserve-like liabilities (e.g., reverse repos) that would also need to be soaked up. As best I can tell, this would not change the qualitative result. The Fed’s saving grace is the growth of currency in circulation since the early 2010’s, now about $2.3 trillion, which does not pay interest and would not need to be soaked up.